#FieldStories: We invited our Field Officer, Bianca, to share her learnings in Oceanus Conservation and working alongside people and nature.

I am Bianca, a Field Officer for Oceanus’ AI/Machine Learning-Powered Digital Monitoring of Mangrove Ecosystems in Surigao del Sur, Philippines Project. As a Field Officer, I am tasked with conducting on-the-ground work such as collecting mangrove data and facilitating the rehabilitation work.

My role extends beyond the technical aspects of mangrove rehabilitation and conservation. It is about fostering genuine connections, engaging in meaningful conversations, and building relationships that are the lifeblood of this project. From educating the community on effective rehabilitation methods to sharing meals and stories, these interactions have profoundly shaped my experience.

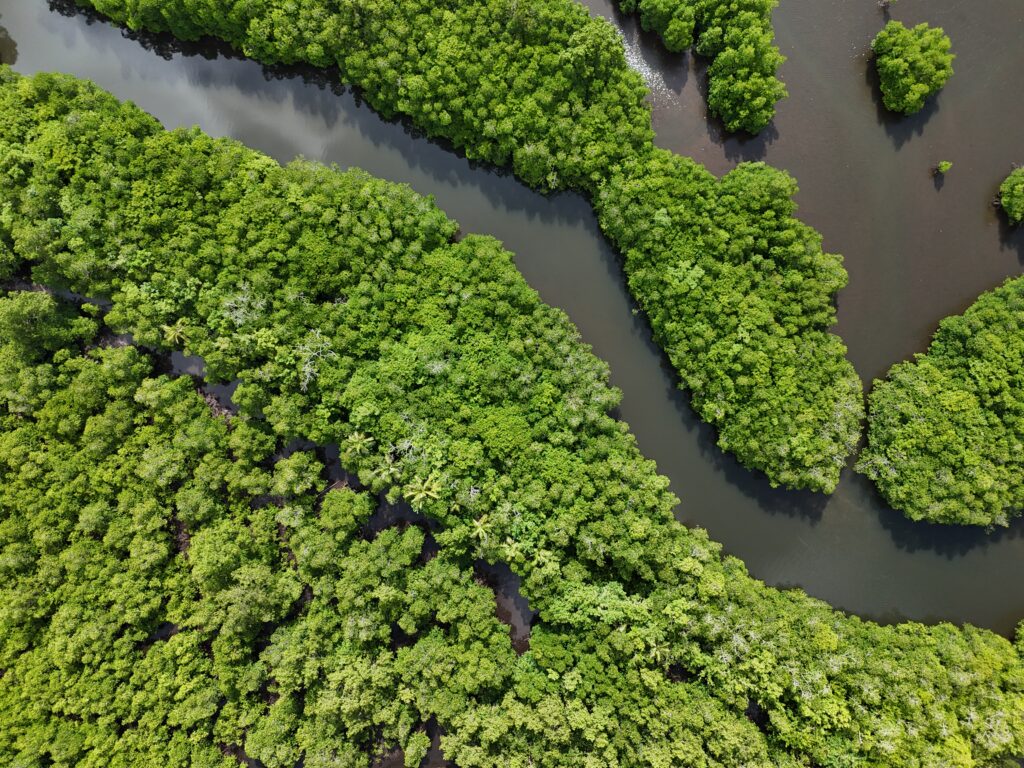

Figure 1. Glimpse of our rehabilitation site in Barangay Bucto, Bislig City.

Our project site is in Bislig City, a coastal area in Surigao del Sur. Facing the Pacific Ocean, the province is particularly vulnerable to natural hazards such as floods and tsunamis. In particular, the likelihood that Surigao del Sur will be hit by a destructive tsunami in the next 50 years is greater than 40% (ThinkHazard.org). Mangroves serve as the area’s natural barrier, offering protection against these calamities.

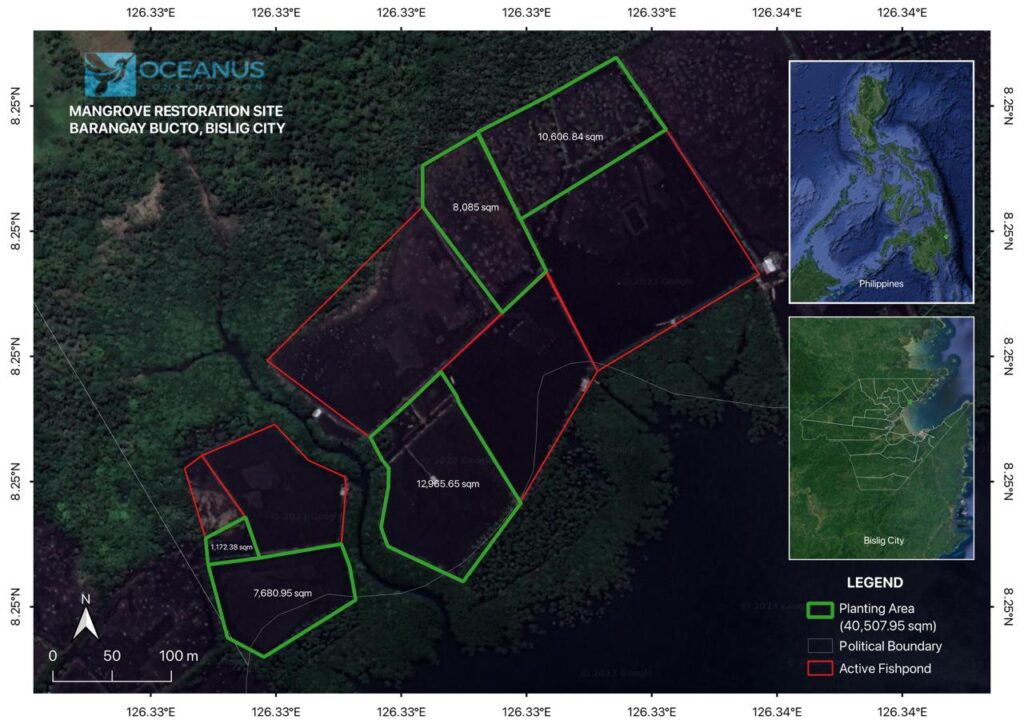

Our rehabilitation site is in Barangay Bucto, approximately 30-40 minutes from the city center. For our mangrove planting activity, we partnered with their village head, Barangay Captain Vicenta Odares, the Bucto Farmers Producers and Producers Cooperative (BUCFAFO), and fishpond operators.

Figure 2. Barangay Bucto Rehabilitation Site. Map by Kathrina Lacson.

What It Is Like As A Field Officer

Our rehabilitation fieldwork ran from February to early May 2025. For more than one month, we made Barangay Caguyao’s Multi-Purpose Hall our home—where we cooked our meals before and after fieldwork, processed the data we collected from the field, and slept.

Our days typically start before sunrise, with everyone in our team pitching in to prepare breakfast. Afterwards, it would take our team 10-15 minutes to get to Brgy. Bucto’s “tugbongan” (docking place for boats). Once there, we would start on our 30-minute walk towards the fishpond area to reach our planting site. Upon arriving at the site, we would find our fishpond operator partners already hard at work, raising the soil in inundated areas to form mounds.

Figure 3. Community members at work on our mangrove rehabilitation project

In order to be more efficient and productive on the field, we would conduct briefings with the community a day before to align on the tasks to be accomplished on site – what time we will meet, how many seedlings we should transfer to the planting area, among others. For our first planting site, we had to transport seedlings approximately 100 meters away from our mangrove nursery. We were accomplishing two things at once – our partners were forming mounds while members of BUCFAFO were diligently transferring mangrove seedlings via a wooden canoe in order to ready them for planting.

Figure 4. Wooden canoe used for transporting seedlings from the nursery to the planting site

As time progressed, our time with the community went beyond formal engagement. Each visit would then begin with warm smiles and greetings from the community– a welcome that has always been indescribable to me. There was a shared shyness initially, but a few light-hearted banters quickly transformed our interactions into enjoyment while working together under the heat of the sun.

Working under 40 degrees Celsius, often followed by a sudden downpour of rain, made our job on the ground physically demanding. If it is already challenging for me, I can only imagine how much our community partners had to endure, especially since they were predominantly older (40+ years old). Yet, their dedication to accomplish as much on the field remained unwavering. For instance, despite the old age of our partner fishpond operators, I saw how determined they were in digging and carrying blocks of soil under the direct heat of the sun to form mounds. Witnessing their growing awareness and commitment to mangrove planting, despite extreme weather, made our exhausting days worth it and even more meaningful.

Figure 4. Field team working with community members (GIF by Andreu Bayongasan)

Food has proven time and again that it is one of the best ways to connect with people. After a tiring time on the field, it was shared meals that brought our team closer to our community partners. Our conversations with them flowed more naturally, and our relationship with them grew stronger. I’ll never forget their constant concern, always asking, “Ma’am, namahaw na mo?” (Ma’am, have you had breakfast?), or offering, “Oh pag snack sa mo” (Please have a snack).

Over time, this concern and generosity did not just come from politeness; it resulted in friendship as well. One thing I could not forget, one fishpond operator told us, “Ayaw na mo magbalon ug sud-an ugma kay maghatag mi ug alimango” (Don’t bring a packed lunch tomorrow because we’ll give you crabs). They even invited us to celebrate with them, by sharing with us “usa ka case og beer” (one case of beer) after they were paid for planting and mounding. Eating together became a pathway to building a better working relationship with the community, immersing myself in the local culture, and most importantly, earning their trust.

Figure 5. Rooted In Purpose. Growing With The Community. (Photo by Bianca Mercado and Andreu Bayongasan)

It’s More Than Just Science

When I look back at the baseline data we collected after planting, especially the aerial drone images, I fondly remember all the hard work our team shared with the community. Drone imagery offers a bird’s-eye view of our work on the ground. For our project, we want to see the potential of AI-based monitoring using drone images. That is well and good, but to me, it means so much more, and this method truly highlighted the collective effort we all poured into this meaningful project.

As an Oceanus Conservation Field Officer, the whole rehabilitation experience allowed me to reflect on values that extend beyond the scientific principles and methods I learned as a marine biologist. While conservation of the environment is the ultimate goal, I learned that this is inextricably linked to the well-being of the people who depend on and thrive within these ecosystems. Community-building has become something I deeply value now, recognizing that successful projects are impossible without the active participation and commitment of local communities. They serve as the “middlemen” – bridging the vision of rehabilitation efforts by organizations like Oceanus – with reality.

The impact we leave on a community reflects how deeply and genuinely we have connected with them. Fieldwork has evolved into something far grander than just science; it’s about connection, purpose, and impact.

This has been one of the most important lessons I’ve gained from being part of Oceanus Conservation, both personally and professionally. With immense gratitude to Oceanus Conservation, I say, “Daghan salamat, dili gyud ko makalimot sa akong mga nabal-an.” (Thank you very much, I will never forget what I have learned.)

Reference

Thinkhazard.org. (n.d.). Surigao del Sur. Retrieved from https://www.thinkhazard.org/en/report/24278-philippines-region-xiii-caraga-surigao-del-sur/TS

#mangroverehabilitation #mangroves #AIforEnvironment #machinelearning #SurigaoDelSur #Philippines